There is substantial research that emphasizes that the burden of climate change will be disproportionately felt by low-income and marginalized populations. [1,2] Much of the dominant discourse on climate change conceptualizes it as an “issue of North-South” relations in that the Global North is the primary driver of climate change while the Global South bears the impacts. [3]

While the importance of this dichotomy cannot be overstated, the focus here will be on the effects of climate change experienced by vulnerable populations within Canada to offer an introduction to the kinds of dynamics we are most likely to see in our future practice.

Chapters

1.

Introduction

2.

Indigenous Peoples

3.

Women

4.

Environmental Displacement

1. Introduction

Understanding Vulnerability to Climate Change

The Intergovernmental panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defines climate vulnerability as the propensity or predisposition to be adversely affected by climate variability and change. Vulnerability to climate-related health consequences is based on exposure to hazards associated with a changing climate, susceptibility to harm, protective factors and the capacity to adapt to or to cope with change. [1]

All Canadians are at risk from the health impacts of climate change. That said, certain populations will disproportionately feel its effects, [2] for example:

- Women

- Children and Infants

- Elders

- People living with chronic diseases

- People with respiratory conditions

- LGBTQ2S+ people

- Indigenous people

- People living in poverty

- Environmentally displaced people (Climate Refugees)

- People living in Northern and remote communities

References

[1] Organization, World H. Protecting Health from Climate Change: Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment. World Health Organization, 2013.

[2] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), 2014.

[3] Williams, L., Fletcher, A., Hanson, C., Neapole, J., and Pollack, M. (2018), Women and climate change impacts and action in Canada: feminist, Indigenous and intersectional perspectives.

2. Indigenous Peoples

Disproportionately Affected by Climate Change

Climate change poses a major threat to Indigenous communities and ways of life in Canada. Based on the multitude of severe ecological, sociocultural, and health impacts of climate change on Indigenous populations, the IPCC, the WHO, and the UN have categorized these groups of people as significantly vulnerable to its effects . That said, representation of Indigenous people in the context of climate change that fails to include a discussion of colonialism and racism as structural causes of vulnerability wrongly portrays the impacts of climate change “as a problem for, rather than of society”. [1]

Systemic Consequences

It is critical to recognize that the social, economic and health inequalities among Indigenous people in Canada are the result of systemic forces of colonialism and oppression and are responsible for subsequently increasing the vulnerability of these diverse communities to the impacts of climate change.

Increased vulnerability to climate change is a result of:

- Canada’s Colonial History:

- The Indian Act

- The Sixties Scoop

- Indian Hospitals

- Residential Schools

- Intergenerational Trauma

- Racism

- Marginalization and subjugation of Indigenous Peoples

- Lack of Indigenous representation in policy-making and government

- Loss of land and language & cultural assimilation secondary to Canada’s colonial history

An Overview of Climate Change and Indigenous Health

Extreme weather events such as heatwaves, storms, floods, droughts, and wildfires have significant implications for conditions like asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiovascular disease – all of which are more prevalent in Indigenous communities, as a direct result of colonialism, systemic racism and discrimination in addition to loss of land and the “traditional practices required for health”. [3-6]

- Melting permafrost in Northern regions jeopardizes community infrastructure and may impact health and wellness if access to health services are compromised. [7] Furthermore, the permafrost melt coupled with changing sea-ice conditions is resulting in increased risks associated with traditional fishing and hunting practices and is undermining Indigenous food sovereignty. [8]

- Sea level rise is endangering coastal communities and is threatening to disrupt intergenerational cohesion and cultural integrity as well as amplify poor mental health outcomes associated with displacement. [9]

- Finally, changing temperatures will impact the distribution and availability of natural resources that are “important in Aboriginal subsistence hunting with implications for community health, nutrition and well-being”. [10]

Monitoring Health Outcomes of Climate Change

The establishment of health monitoring and response systems to measure the effects of climate change is an important adaptation strategy that is slowly being implemented in various Indigenous communities across Canada. Given the overwhelming absence of Indigenous voices on matters related to environmental policy-making and planning, the implementation of health monitoring approaches that are founded on Indigenous knowledge systems are critical to reflect their values and therefore meaningfully address their challenges. [11, 12]

References

[1] Belfer, E., Ford, J. D., & Maillet, M. (2017). Representation of indigenous peoples in climate change reporting. Climatic Change, 145(1), 57-70. doi:10.1007/s10584-017-2076-z

[2] Ford, J. D., Cameron, L., Rubis, J., Maillet, M., Nakashima, D., Willox, A. C., & Pearce, T. (2016). Including indigenous knowledge and experience in IPCC assessment reports. Nature Climate Change, 6(4), 349-353. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2954

[3] Loppie Reading, C., & Wien, F. (2009). Health inequalities and the social determinants of aboriginal peoples’ health. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

[4] Ford, J. D., Berrang-Ford, L., King, M., & Furgal, C. (2010). Vulnerability of aboriginal health systems in canada to climate change. Global Environmental Change, 20(4), 668-680. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.05.003

[5] First Nations Health Status & Health Services Utilization. First Nations Health Authority. Retrieved from https://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-First-Nations-Health-Status-and-Health-Services-Utilization.pdf

[6] Earle, L. (2011). Understanding chronic disease and the role for traditional approaches in aboriginal communities. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health.

[7] Canada’s Top Climate Change Risks. The Expert Panel on Climate Change Risks and Adaptation Potential. Retrieved from https://cca-reports.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Report-Canada-top-climate-change-risks.pdf

[8] Lemmen, D. S., Warren, F. J., Canada. Natural Resources Canada, Canada, & Canadian Government EBook Collection. (2014). Canada in a changing climate: Sector perspectives on impacts and adaptation. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada = Gouvernement du Canada.

[9] Ibid 7.

[10] Ibid 4.

[11] Kipp, A., Cunsolo, A., Gillis, D., Sawatzky, A., & Harper, S. L. (2019). The need for community-led, integrated and innovative monitoring programmes when responding to the health impacts of climate change. United States: Taylor & Francis. doi:10.1080/22423982.2018.1517581

[12] Lam, S., Dodd, W., Skinner, K., Papadopoulos, A., Zivot, C., Ford, J., Garcia, P. J., Harper, S. L., & IHACC Research Team. (2019). Community-based monitoring of indigenous food security in a changing climate: Global trends and future directions.Environmental Research Letters, 14(7), 73002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab13e4

3. Women

Gender Inequities & Climate Change

The impacts of climate change are intensifying gender inequities in Canada. The understanding of climate change as a determinant of health can be expanded to conceptualize climate change as a risk multiplier in that it exacerbates inequalities already present in society. [1]

The increased vulnerability of women to a changing climate is best understood by approaching the issue with a gendered intersectional lens; the confluence of social roles, power relations, culture, race, sexual and gender identity as well as socioeconomic status make women disproportionately experience the burden of climate change. [2]

Specifically, overlapping social and economic constraints experienced by poor and marginalized individuals in society significantly limit their capacity to manage and adapt to the repercussions of climate change. Given that women constitute the largest percentage of the world’s poorest people, they are one of the most vulnerable populations to climatic risks. [3]

Canadian Context

Despite the fact that gender is recognized as a health determinant both nationally by Health Canada as well as internationally by the World Health Organization and the United Nations, it remains absent as a distinct category of analysis within Public Health commentaries of climate change impacts and action in Canada. [9] Moreover, there is an overwhelming exclusion of women’s voices and leadership on matters of environmental policy and climate change strategy in Canada. [10] The absence of information on climate change and women underscores the importance of future research that is gender-sensitive.

Heat Waves & Gendered Impacts of Climate Change in Canada:

- Women are more likely than men to live in lower-income housing, rental properties and basement suites and therefore be unable to afford, access or upgrade their homes with sufficient air conditioning systems. [5,6]

- Women of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to live in urban centers and be exposed to the harmful effects of “Heat Islands”. [7]

- Gendered division of household labor implies that women are primarily responsible for caring for the elderly and children during heatwaves. [8]

- Pregnant women are physiologically less tolerant to extreme heat as their ability to thermoregulate is compromised and extreme heat may contribute to: [9]

- Pre-term birth.

- Low birth weight at the time of delivery.

- Increased admission of neonates to ICU.

- Increase in stillbirth rates.

A Global Scale

What we can learn from the United Nations Overview of the Linkages between Gender and Climate Change:

Climate Change and the Gender Gap [4]

- Eighty percent of people displaced by climate change are women.

- Globally, women earn 24 percent less than men and hold only 25 percent of administrative and managerial positions in the business world; 32 percent of businesses have no women in senior management positions. Women still hold only 22 percent of seats in single or lower houses of national parliament.

- Nine in 10 countries have laws impeding women’s economic opportunities, such as those which bar women from factory jobs, working at night or getting a job without permission from their husbands.

- A study using data from 219 countries from 1970 to 2009 found that, for every one additional year of education for women of reproductive age, child mortality decreased by 9.5 percent.

- Over four million people a year die prematurely due to illness caused by indoor air pollution, primarily from smoke produced while cooking with solid fuels.

- More than 70 percent of people who died in the 2004 Asian tsunami were women. Similarly, Hurricane Katrina, which hit New Orleans (USA) in 2005, predominantly affected poor African-Americans, especially women.

- Women do not have easy and adequate access to funds to cover weather-related losses or adaptation technologies. They also face discrimination in accessing land, financial services, social capital and technology.

References

[1] Perkins, P.E. (2015). Gender and Climate Justice in Canada. Climate Change, Gender and Work in Rich Countries. Retrieved from https://www.sfu.ca/content/dam/sfu/climategender/WorkingPapers/2017/WP-Perkins.pdf

[2] UNDP . Training Module 1—Overview of Linkages between Gender and Climate Change, Global Gender and Climate Alliance. United Nations Development Programme; Gender and Climate Change.

[3] Ibid 2.

[4] Ibid 2.

[5] Rochette, A. (2016). Climate change is a social justice issue: The need for a gender-based analysis of mitigation and adaptation policies in canada and quebec. Journal of Environmental Law and Practice, 29, 383.

[6] Gronlund, C. J., Sullivan, K. P., Kefelegn, Y., Cameron, L., & O’Neill, M. S. (2018). Climate change and temperature extremes: A review of heat- and cold-related morbidity and mortality concerns of municipalities. Maturitas, 114, 54-59. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.06.002

[7] Ibid 5.

[8] Kuehn, L., & McCormick, S. (2017). Heat exposure and maternal health in the face of climate change. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(8), 853. doi:10.3390/ijerph14080853

[8] Ibid 5

[9] Whyte, K. P. (2014). Indigenous women, climate change impacts, and collective action. Hypatia, 29(3), 599-616. doi:10.1111/hypa.12089

4. Environmental Displacement

Climate Migrants

Climate change has displaced an average of 26.4 million people around the world every year since 2008. The 2020 World Migration Report issued by the International Organization for Migration details that climate related disasters are responsible for the displacement of more people than war and conflict related events.[1] By 2050, the United Nations estimates that there will be as many as 1 billion climate migrants. [2]

Climate Migrants are unwillingly forced from their homes by the climate emergency, are fleeing situations in which their health is put at risk, but subsequently find their health threatened by the vagaries of an international system that is struggling to keep pace with the many harmful aspects of the climate crisis. [3]

“The most vulnerable households are able to use migration to cope with the environmental stress, but their migration is an emergency response that creates conditions of debt and increased vulnerability, rather than reducing them.”

— Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [25]

Postmigration

Postmigration factors, such as access to housing, employment and a sustainable income, language skills and social support, as well as experiencing discrimination and social isolation, must also be considered to understand the psychological effects of the refugee experience. The asylum system, however, is unpredictable and is characterized by a lack of transparency as well as individual control. Someone else, usually a refugee programme administrator or service provider, tells you where to live and how to fill your days. Another person decides your fate, on grounds that are often arbitrary and hard to understand. Most asylees find it difficult to seek help and use services because of the aforementioned heightened sense of distrust and insecurity. Moreover, the operational difficulties such as language barrier and lack of secure and safe relationships, make it more difficult to connect again to others in the new host country. [14]

Understanding the intersection between global migration & health

Selected examples based on information presented in the UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration & Health [14]

Youth Health

The maitenance of family units and access to education and health services is foundational to positive health outcomes in migrant youth.

Stigma and social exclusion experienced by adolescents can contribute to emotional distress, anxiety, depression, self-harm and suicide.

Perinatal Health

Perinatal outcomes among migrants and refugee women compared with the host population found worse outcomes among migrants for maternal mortality, maternal mental health, postpartum depression, preterm birth, and congenital anomalies.

Potential reasons for adverse outcomes include:

- Stress and burden of migration

- Underlying heart disease or HIV

- Poor access to and interaction with health care services

- Loss of social support systems in community of origin

- Communication barriers

- Socioeconomic status

Mental Health

First-generation international migrants tend to have higher prevalence rates of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder compared with the host population.

LGBTQ2S+ Health

The absence of data on LGBTQ+ migrant individuals speaks to the unacceptable disregard of this population in much epidemiological data to date.

“Sexual minorities might be among the most neglected and at-risk populations in circumstances of migration. The stigma associated with being LGBTI can subject individuals to bullying and abuse or force them to remain invisible. There appears to be little training for health and humanitarian aid professionals currently to meet the health needs of sexual minorities…We know very little, for example, about the health of undocumented migrants, people with disabilities, or lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, or intersex (LGBTI) individuals who migrate or who are unable to move.”

— Lancet Commission on Migration & Health

Recognizing Displacement in a Climate Context: The Syrian War

In 2007, Syria experienced a major drought that lasted several years and resulted in the mass migration of internally displaced people towards urban city centers. [4] Precipitation, temperature and sea-level pressure data collected over a century in the area confirmed that the probability of this kind of relentless drought was increased by a factor of 3 due to climate change. [5]

The influx of 1.5 million people from rural farming areas toward urban centers destabilized the fragile social, economic and political fabric of Syria. The urban peripheries of major cities in Syria were inundated by displaced people and characterized “by illegal settlements, overcrowding, poor infrastructure, unemployment, and crime”. [6] These settlements were “neglected by the Assad government and became the heart of developing unrest” that galvanized the onset of the Syrian civil conflict in 2011 and eventually led millions of people to flee the country. Ultimately, the confluence of climate change, water mismanagement, a decline in crop yield and of livestock herds, unstable farming practices and a repressive government regime were largely responsible for driving people from their homes and destroying their livelihoods. [7]

The United Nations Refugee Agency attributes the increase in forcibly displaced people from 43.3 million in 2009 to 70.8 million in 2018 primarily to the Syrian conflict. [11] In 2018, Canada admitted the largest number of resettled Syrian refugees (28,100 out of the documented 92,400 refugees). [12]

Arrival to Canada – or any other country of asylum – does not necessarily imply an easy fix to the number of health concerns described by the International Organization for Migration. The profound stress and uncertainty inherent in fleeing one’s home – compounded with the difficulties of navigating language and cultural barriers and coping with stigma in their country of asylum – shapes future health outcomes in refugees. [13]

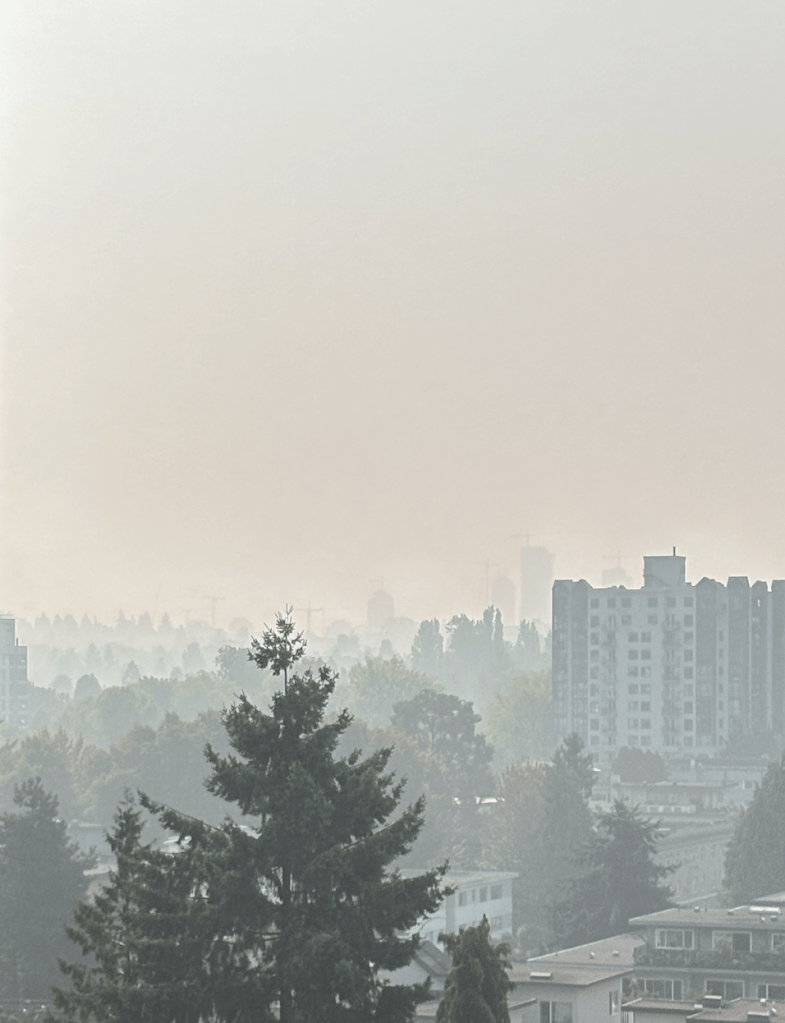

Displacement in a Climate Context: Canadian Wildfires

In 2017, an overwhelming 12,000 square kilometers was burned in British Columbia during the wildfire season. While the dryer weather in the summer months naturally results in forest fire activity, climate change has increased the area burned by a factor of 7-11. [15] The destruction of land resulted in the displacement of 65,000 people.[16] The forest fire season of 2018 burned 13,000 square kilometers of land, surpassing the record-breaking devastation caused by the year earlier and caused the provincial government of British Columbia to declare a state of emergency. [17]

Some of the Health Effects of Wildfires:

- Direct Injury and death from contact with fire

- Exacerbation of chronic respiratory and cardiac conditions

- Wildfire smoke can increase pollutant levels up to 10-fold and contains particulate matter, which has damaging cardiopulmonary effects. [18,19] Smoke inhalation has been shown to increase respiratory morbidity and mortality, in addition to an increased risk of cardiovascular incidents, such as cardiac arrest. [20,21]

- Stress of displacement

- Evacuees and communities on the periphery of wildfires in evacuation limbo experience prolonged stress associated with increasing rates of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. [22] Ensuring that mental health professionals play a role in wildfire response and are readily available for patients in affected areas, contributes to positive health outcomes in these individuals. [23] Patients at a higher risk of mental health illnesses following wildfire (such as those with pre-existing mental health conditions) benefit from early intervention and support. [24]

What can we do as medical students?

Research, ask questions, and continue learning. As underscored by the UN Commission on Migration and Health: education on climate change and migrant health is of paramount importance.

The current gaps in knowledge about how climate change events catalyze mass migration movements, and the subsequent health challenges these migrants face, present a barrier for supporting these individuals in their transition.

Examples of areas that require further research:

- The health implications of laws governing environmentally displaced people and Canadian policy on climate change related asylum claims.

- As of January 2020, the United Nations Human Rights Committee has ruled that governments cannot return people to countries where their lives might be threatened by climate change. [26]

- Perspectives and perceptions of displaced people to understand how and to what extent environmental changes in their countries of origin contributed to their decision to leave their homeland. [27]

- The implications of acknowledging climate change with refugees in the clinical setting – what are possible harms or benefits to patients?

References

[1] United Nations, & desLibris – Documents. (2019;2020). World migration report 2020. New York; Blue Ridge Summit; United Nations Publication.

[2] Lancet, T. (2020). Climate migration requires a global response. The Lancet, 395(10227), 839-839. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30571-7

[3] Ibid 2.

[4] Morisetti, N., & Blackstock, J. J. (2017). Impact of a changing climate on global stability, wellbeing, and planetary health. The Lancet Planetary Health, 1(1), e10-e11. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30006-2

[5] Kelley, C. P., Mohtadi, S., Cane, M. A., Seager, R., Kushnir, Y., & Columbia Univ., New York, NY (United States). (2015). Climate change in the fertile crescent and implications of the recent syrian drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(11), 3241-3246. doi:10.1073/pnas.1421533112

[6] Ibid 5.

[7] Wendle, J. (2016). Syria’s climate refugees. Scientific American, 314(3), 50-55. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0316-50

[8] Kirchmeier‐Young, M. C., Gillett, N. P., Zwiers, F. W., Cannon, A. J., & Anslow, F. S. (2019;2018;). Attribution of the influence of Human‐Induced climate change on an extreme fire season. Earth’s Future, 7(1), 2-10. doi:10.1029/2018EF001050

[9] Climate Change Canada. (2019, January 8). Canada’s scientists conclude that human-induced climate change had a strong impact on forest fires in Briti… Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/news/2019/01/canadas-scientists-conclude-that-human-induced-climate-change-had-a-strong-impact-on-forest-fires-in-british-columbia.html

[10] 2018 now worst fire season on record as B.C. extends state of emergency | CBC News. (2018, August 29). Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/state-emergency-bc-wildfires-1.4803546

[11] Global Trends in Forced Displacement. The United Nations Refugee Agency. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/5d08d7ee7/unhcr-global-trends-2018.html?query=canada

[12] Global Trends in Forced Displacement. The United Nations Refugee Agency. Retrieved from https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/5d08d7ee7/unhcr-global-trends-2018.html?query=canada

[13] Cange, C. W., Brunell, C., Acarturk, C., & Fouad, F. M. (2019). Considering chronic uncertainty among syrian refugees resettling in europe. The Lancet Public Health, 4(1), e14-e14. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(18)30261-5

[14] Abubakar, I., Aldridge, R. W., Devakumar, D., Orcutt, M., Burns, R., Barreto, M. L., Dhavan, P., Fouad, F. M., Groce, N., Guo, Y., Hargreaves, S., Knipper, M., Miranda, J. J., Madise, N., Kumar, B., Mosca, D., McGovern, T., Rubenstein, L., Sammonds, P., . . . UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health. (2018). The UCL–Lancet commission on migration and health: The health of a world on the move. The Lancet (British Edition), 392(10164), 2606-2654. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7

[15] Kirchmeier‐Young, M. C., Gillett, N. P., Zwiers, F. W., Cannon, A. J., & Anslow, F. S. (2019;2018;). Attribution of the influence of Human‐Induced climate change on an extreme fire season. Earth’s Future, 7(1), 2-10. doi:10.1029/2018EF001050

[16] Climate Change Canada. (2019, January 8). Canada’s scientists conclude that human-induced climate change had a strong impact on forest fires in Briti… Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/news/2019/01/canadas-scientists-conclude-that-human-induced-climate-change-had-a-strong-impact-on-forest-fires-in-british-columbia.html

[17] 2018 now worst fire season on record as B.C. extends state of emergency | CBC News. (2018, August 29). Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/state-emergency-bc-wildfires-1.4803546

[18] Liu JC, Mickley LJ, Sulprizio MP, et al. Particulate air pollution from wildfires in the Western US under climate change. Clim Change 2016;138:655-66

[19] Dennekamp M, Abramson MJ.2011The effects of bushfire smoke on respiratory health. Respirology 16198–209.;10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01868.x

[20] Reid, C. E., Brauer, M., Johnston, F. H., Jerrett, M., Balmes, J. R., & Elliott, C. T. (2016). Critical Review of Health Impacts of Wildfire Smoke Exposure. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(9), 1334–1343. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409277

[21] Haikerwal, A., Akram, M., Monaco, A. D., Smith, K., Sim, M. R., Meyer, M., … Dennekamp, M. (2015). Impact of Fine Particulate Matter (PM 2.5 ) Exposure During Wildfires on Cardiovascular Health Outcomes. Journal of the American Heart Association, 4(7). doi: 10.1161/jaha.114.001653

[22] Galea, S., Brewin, C. R., Gruber, M., Jones, R. T., King, D. W., King, L. A., et al. (2007). Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after hurricane Katrina. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(12), 1427–1434.

[23] Tally, S., Levack, A., Sarkin, A. J., Gilmer, T., & Groessl, E. J. (2012). The Impact of the San Diego Wildfires on a General Mental Health Population Residing in Evacuation Areas. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40(5), 348–354. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0425-9

[24] Dirkzwager, A. J., Kerssens, J. J., & Yzermans, C. J. (2006). Health problems in children and adolescents before and after a manmade disaster. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(1), 94–103.

[25] Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2018.

[26] UN human rights ruling could boost climate change asylum claims | | UN News. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/01/1055671

[27] Climate Change, Vulnerability and Human Mobility: Perspectives of Refugees from the East and Horn of Africa. https://www.unhcr.org/protection/environment/4fe8538d9/climate-change-vulnerability-human-mobility-perspectives-refugees-east.html